Combating fake news isn’t a new issue — historically, we’ve been battling various versions of made-up information since the invention of the printing press, and in America since the 1800s. But the amount of fake or badly written news, and the speed with which it spreads, has increased in the new millennium.

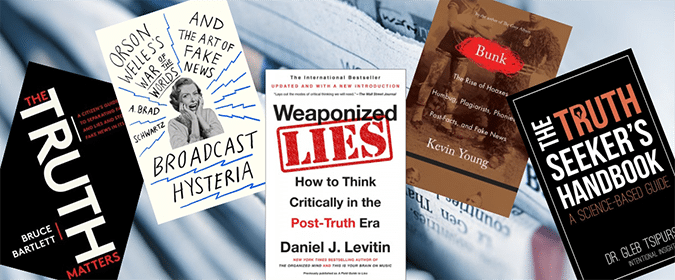

It’s now up to the readers as much as the journalists to make sure the facts are there and being interpreted correctly. Journalists are constantly tweeting tips for readers, and some have even written essays on “cut[ting] through the bullshit” to help readers think more like reporters. We’ve also seen a slew of books written about the modern fake news problem, some better than others. To help you cut through the crap, we’ve rounded up the top five books in the ever-more-crowded field of fake news analysis.

Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News by Kevin Young

Key quote: “It isn’t that the contemporary hoax provides ‘a different kind of truth’ but that it offers far less. A whole lie would almost be welcome, but hoaxes won’t extend us the courtesy of respecting the truth enough to betray it. Instead, we have become surrounded by the halfway, mealymouthed, politicking habit of bullshit.”

Who wrote this? Kevin Young is the current poetry editor for The New Yorker, as well as the director for the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the author of a dozen books of poetry and prose.

What’s it about? Broken into six parts, Bunk explores the history of fake news, from the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, the hustlers and hoaxsters of the early 20th century, all the way through modern-era plagiarists and fabulists. P.T. Barnum and Orson Welles share space with J.T. LeRoy, Jayson Blair, Janet Cooke and Stephen Glass in Young’s recounting of the stories that fooled Americans over time, though he makes a point of delineating the differences between the public figures and journalists (or “journalists”). If it’s a fake news story, Young explores it and explains its impact on the people and on journalism.

What you’ll get out of it: While it may be depressing to realize just how far back in our history the fake news phenomenon goes, it’s comforting knowing we’ve managed to maintain or regain trust in the press through each of these moments. The historical context also comes in handy in tracing how we progressed from the great big hoaxes of the 1800s to the more intentional and detrimental fake news of 2018.

Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News by A. Brad Schwartz

Key quote: “It is certainly true that, in the early days of radio, newspapers fought hard to keep broadcasters from reporting the news by restricting access to the wire services. Hostility between the two mediums bubbled up in the early 1930s in a series of legal battles that historians call ‘the Press-Radio War.’ For the first time since Gutenberg, new technology had prompted a major realignment in how people consumed news and information. Those in more established media struggled to adapt. Some were scared to death of it. ‘Newspaper publishers had better wake up,’ warned one Tennessee publisher in 1932, ‘or newspapers will be nothing but a memory on a table at Radio City.’

Who wrote this? A. Brad Schwartz is a doctoral student in American history at Princeton University. In addition to writing Broadcast Hysteria, Schwartz co-wrote a PBS American Experience episode about Orson Welles’s infamous radio broadcast. He is currently writing a dual biography of Al Capone and Eliot Ness.

What’s it about? Everyone knows the story of how Orson Welles’s radio production of The War of the Worlds was mistaken as news and scared the American public — or do they? Schwartz, through access to the original letters sent to Welles, as well as other historical documents and interviews, traces the supposed hysteria of that fateful evening in 1938 and its impact on modern media. But it isn’t all about Welles. Schwartz also tracks how newspapers reacted to their new broadcast brethren and discusses a bit of what’s happening today, as fake news proliferates and newspapers fight the internet to be top media dog.

What you’ll get out of it: The Press-Radio War of the 1930s will likely remind you of the ongoing print vs. digital battle of the 21st century, and that alone will give you some insight into how to move forward in this strange time where not all news publishers feel they have equal footing.

The Truth-Seeker’s Handbook: A Science-Based Guide by Gleb Tsipursky

Key quote: “We may think we want the truth, but sometimes the facts can be very difficult to handle, since they cause us very unpleasant emotions and make us really uncomfortable. Our minds tend to flinch away from these facts, preferring instead to seek out the comfort of our pre-existing beliefs. Being a truth-seeker involves undertaking the sometimes-difficult work of expanding one’s comfort zone and challenging one’s pre-existing notions for the sake of seeing the truth of reality.

Who wrote this? Dr. Gleb Tsipursky is an assistant professor at Ohio State University and the creator of the Pro-Truth Pledge, which encourages public figures to commit to telling the truth and only sharing fact-based information.

What’s it about? Tsipursky takes lead on this book featuring nine other writers sharing their thoughts on how we think. Over the course of 260 pages and more than 40 chapters, Tsipursky and company share insights on how to think more rationally and ignore our preconceived notions in favor of getting to the truth. They cover such matters as when to follow your gut versus going with your head; how cognitive bias and delusion keep us from learning; and how we sometimes operate on autopilot and other times intentionally, and what those modes do to how we perceive the information we take in, including how we take in the news.

What you’ll get out of it: Forty-plus chapters seems like a lot, but each one is no more than a few pages long, meaning you can skip around and read the parts that you feel apply to you. You’ll finish with lots of things to think about — like why you’re thinking about those things to begin with. It’s a little meta at times, thinking about thinking, but it just may help you rethink how you respond to information you agree with, and information that you don’t.

Weaponized Lies: How to Think Critically in the Post-Truth Era by Daniel J. Levitin

Key quote: “There are not two sides to a story when one side is a lie. Journalists — and the rest of us — must stop giving equal time to things that don’t have a fact-based opposing side. Two sides to a story exist when evidence exists on both sides of a position. Then, reasonable people may disagree about how to weigh that evidence and what conclusion to form from it. Everyone, of course, is entitled to their own opinions. But they are not entitled to their own facts. Lies are an absence of facts and, in many cases, a direct contradiction of them.”

Who wrote this? Daniel J. Levitin is a cognitive neuroscientist, a professor of psychology and behavioral neuroscience at McGill University; the dean of social sciences at Minerva Schools at KGI; a faculty member at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business; and a best-selling author. Essentially, he’s an expert on how and why we think the way we do.

What’s it about? Weaponized Lies covers three important areas of learning how to debunk fake news: evaluating numbers, words and, finally, the world. Each part breaks down what to look for to know if what you’re reading deserves to be treated as relevant fact, half-truth or outright fiction. By explaining how bad actors can fool us, through manipulation of words and data, into thinking a certain way, Levitin teaches readers how to better analyze the information being presented to them and get to the truth, even if it isn’t clearly spelled out.

What you’ll get out of it: There is so much to be learned from Levitin’s book! The opening section on

“how numbers and charts can be misleading” is by far the best explanation of analyzing data you’ll find, and it’s simple enough to appeal to laymen while being smart enough to make even seasoned data journalists think twice about how they present information. This should be required reading for everyone who consumes news.

The Truth Matters: A Citizen’s Guide to Separating Facts from Lies and Stopping Fake News in Its Tracks by Bruce Bartlett

Key quote: “If the concept of fake news is not new, its current techniques are. The internet and social media have made it very easy to peddle and promote lies. Although theoretically these same methods ought to enable truth to win out in the end, in practice this has proven not to be the case. Political scientists have found that when people who have been exposed to lies are confronted with the truth, they often believe the lie even more strongly. One reason is that simple repetition of a lie, even in the course of refuting it, lends it credibility. Another reason is confirmation bias — people believe what they want to believe.”

Who wrote this? Bruce Bartlett is a Washington, D.C., insider with more than 40 years spent working on Capitol Hill. He’s the best-selling author of a handful of books about the American economy, tax reform and the Republican legacy after President Ronald Reagan. He’s also been interviewed numerous times about his work, so he knows a thing or two about how the news sausage gets made.

What’s it about? Bartlett breaks down journalistic conventions for the average person, helping readers understand the terminology they may come across while reading or watching the news. He gives context to uses of different types of sources and ways of obtaining information, and explains why and how journalists might use each — as well as how different types of information can be misused to create biased or fake news.

What you’ll get out of it: If you’re a news pro, you won’t learn much you don’t already know, but you will learn to think more like your readers, which will be helpful for making sure you’re not mistaken as fake news. Non-pros, however, will get a better understanding of how the news gets written and what to look for to be sure they’re getting something with substance and not just propaganda.