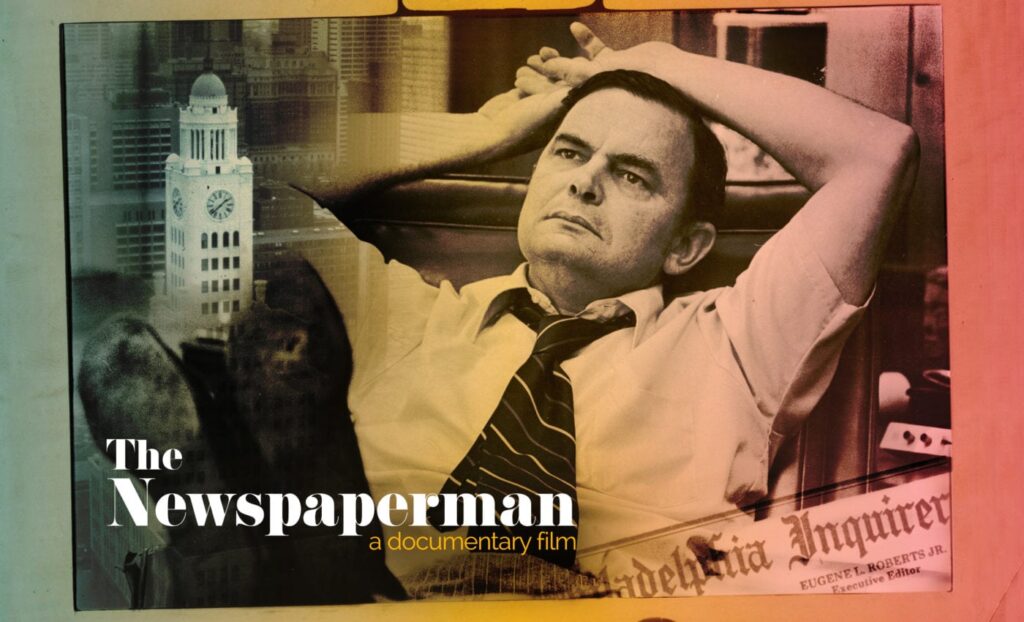

David Layton and Mike Nicholson are kickstarting the documentary The Newspaperman. They are co-producing and directing. The film will tell the story of newspaper editor Gene Roberts. Roberts is known for turning around the Philadelphia Inquirer in the 1970s to become one of the best regional papers in the country. The Alliance spoke with the filmmakers about the project in this edition of 5 Answers.

1 What inspired this film?

DAVID: I’ve known about Gene since I was a child. My father worked at the Inquirer, and Gene was always a sort of larger than life figure to me growing up. It was only when I was much older and my father had retired that I understood just how unique the Inquirer was then. I began to see how Roberts motivated that talented and eclectic group of journalists to do some pretty great things. So I had been kicking this story around in my head for years before we decided to jump in and make the film.

MIKE: I’d been wanting to make a film dealing with media in some way for a long time, so when David first pitched the idea of a film about Gene and the turnaround of the Inquirer, I was interested. But it wasn’t until we were actually interviewing Gene at his home in North Carolina that it really clicked how his story could be a vehicle to explore the broader ideas around the role the media plays in our culture. What happened at the Inquirer is maybe the best example of why journalism is so essential to the functioning of our society and our democracy.

2 What do you want the audience to walk away with?

MIKE: We hope folks come away from this film with a firm understanding of not just what constitutes good journalism, but why good journalism is important. It’s like what Davis “Buzz” Merritt said to us during our interview with him: “Democracy cannot function without an effective journalism involved in it.”

When we began this project, “fake news” wasn’t really a concept people talked about. The antagonism toward science, provable facts, and a combative and robust press wasn’t nearly as prevalent. We want to show why it’s important to have an institution that has as its primary objective to inform citizens about what’s going on in their world by digging for information, challenging assumptions, and constantly confirming facts. It’s the only real check against corruption and malfeasance by the powers that be.

3 How do you think newspapermen (and women) have changed, and is it for the better?

DAVID: We call the film, “The Newspaperman” because Roberts was thoroughly and completely a newspaper journalist. He wasn’t a broadcaster, he didn’t work on magazines, and he isn’t mostly known for his books. He worked on daily papers with hard deadlines that went out every day – filled with news and features and box scores and classifieds and department store ads and comics and a TV guide book.

Newspapers in his day were a big part of a community and tied its people together. It had something for everybody. If you were leafing through a paper, looking for the job listings or the recap of a ballgame, you would still see a story about peace talks in the Middle East or a story about the zoning board approving a new development, or whatever.

Newspapers have a solemn obligation to report the news, investigate corruption, and to keep tabs on politicians and business leaders, but also a quotidian obligation to give people details about the house fire down the street and the high school choral concert.

Reading the paper was a ritual for many, many people. Newsstands and honor boxes could be found in every neighborhood, on many street corners. Gene inhabited that world and understood it completely. He believed in the role of a newspaper in a community. Now, all that is mostly gone. I think online journalists and documentary filmmakers and even television reporters don’t enjoy that same connection to community that newspaper people did when papers were in their prime and most influential.

4 What inspired you about Roberts’ life?

MIKE: During his early years as a reporter, Roberts covered some of the biggest stories of his era, including the Kennedy assassination, the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. These were stories on which American newspapers had a big effect. He was an editor at a time when newspapers had unprecedented resources and impact, and his innovations were imitated nationwide.

5 Where do you see the future of news media?

DAVID: There have been some great examples of grant-based and donor-based journalism recently. ProPublica and The Texas Tribune are two that come to mind. What’s important is that there is a way for a team of journalists to get paid to come in to work every day to ask questions and look for stories, and that they are protected from pressure and able to work independently and fearlessly. I don’t know that we’ll ever again see a State House teeming with reporters from many different news outlets, pigeonholing legislators so they might understand what a bill means while it’s still in committee. That’s what it takes to really shine a light on a democracy. What I worry about is that if politicians and community leaders get used to not having to answer questions, they will start to consider it something that they’re not obligated to do. I think we’re beginning to see a little bit of that.